A labour recruiter reportedly persuaded Maksudur Rahman to leave the tropical warmth of his hometown in Bangladesh and travel thousands of miles to frigid Russia for a job as a janitor.

Within weeks, he found himself on the front lines of Russia’s war in Ukraine.

Rahman and two other Bangladeshi men who escaped told AP that after arriving in Moscow, they were made to sign documents in Russian that turned out to be military contracts. They were sent to army camps for training in drone warfare, medical evacuation, and combat with heavy weapons.

Rahman protested. Through a translation app, a Russian commander told him, “Your agent sent you here. We bought you."

The men described being forced to advance ahead of Russian troops, transport supplies, evacuate the wounded, and recover dead soldiers. Families of other missing Bangladeshis reported similar experiences.

Neither the Russian Defense Ministry, Russian Foreign Ministry, nor the Bangladeshi government responded to AP’s questions.

Rahman said he and his group were threatened with 10-year jail terms and beaten. “They’d say, ‘Why don’t you work? Why are you crying?’ and kick us,” he said. He escaped and returned home after seven months.

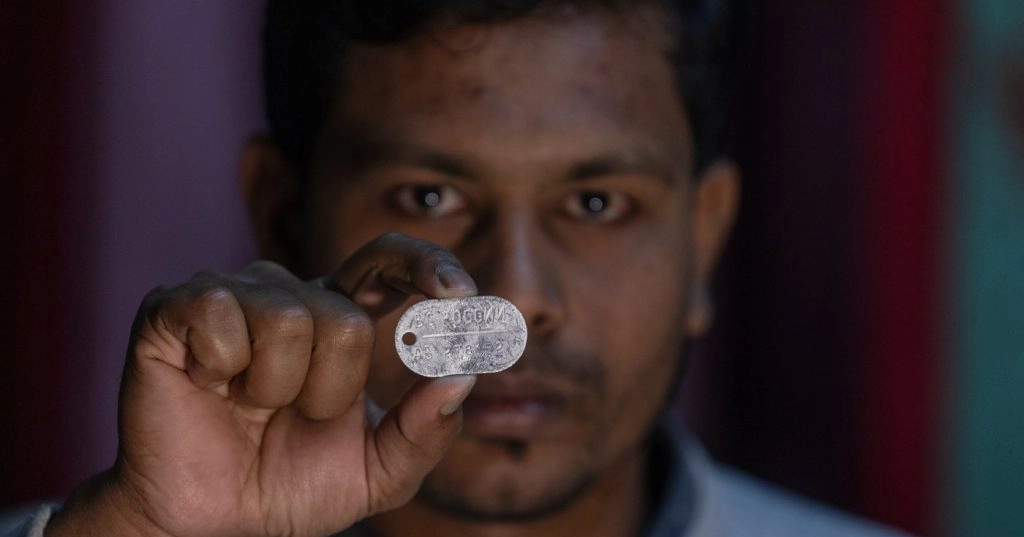

Documents reviewed by AP, including visas, contracts, medical and police reports, and photos, confirm the workers’ accounts. Officials and activists said Russia also targeted men from India, Nepal, and African countries.

In Bangladesh’s Lakshmipur district, many families rely on migrant work. In 2024, Rahman sought new work after a contract in Malaysia. A recruiter offered a job as a cleaner in a Russian military camp with a salary of $1,000 to $1,500 and possible permanent residency. Rahman paid 1.2 million taka ($9,800) to the recruiter and arrived in Moscow in December 2024.

Upon arrival, Rahman and three other men were handed Russian documents, believed to be cleaning contracts, and sent to a military facility for training. They were later deployed near the Russia-Ukraine border, digging pits in bunkers while bombs and missiles struck nearby.

Some workers, like Mohan Miajee, were promised positions far from combat. But after arriving at a camp in Avdiivka, he was told, “You have been made to sign a contract to join the battalion. You cannot do any other work here. You have been deceived,” he said. Miajee was beaten and tortured whenever he refused orders or made mistakes.

Rahman’s unit was later sent to evacuate a wounded Russian soldier, only to be attacked by drones. He suffered a leg injury and escaped via a hospital with help from the Bangladeshi embassy. He later helped his brother-in-law escape in the same way.

Families of missing men cling to visas, contracts, and army documents, hoping they will help bring their loved ones home. Salma Akdar said her husband, Ajgar Hussein, was taken in December 2024 for what he believed was a laundry job. “Seeing all this, he cried a lot and told them, ‘We cannot do these things. We have never done this before,’” she said.

Mohammed Siraj’s 20-year-old son, Sajjad, expected to work as a chef. Instead, he was forced into combat. “That is the last message from my son,” Siraj said. Sajjad later died in a drone attack, news that deeply affected the family.

An investigation by BRAC and Bangladesh police uncovered at least 10 missing men and a trafficking network involving Bangladeshi intermediaries connected to Russia. About 40 Bangladeshis may have died in the war. Families reported receiving no earnings from their relatives’ work.

“I don’t want money or anything else,” Akdar said. “I just want my children’s father back.”